Senior research fellow, professor and author Sandy Pentland joins the podcast to discuss how innovators can leverage shared wisdom and understand human stories to build reliable AI products.

Ready, Test, Go. brought to you by Applause // Episode 34

Stories, Society and the Future of AI

About This Episode

Special Guest

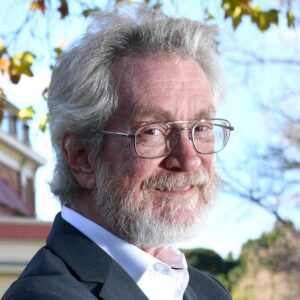

Sandy Pentland

Sandy Pentland is a Stanford HAI Fellow and MIT Professor. Named one of the “100 people to watch this century” by Newsweek and “one of the seven most powerful data scientists in the world” by Forbes, he serves as an advisor to the Abu Dhabi Investment Authority Lab and UN Secretary General’s office.

Transcript

(This transcript has been edited for brevity.)

DAVID CARTY: Cultural representation goes a long way, whether you’re trying to simply understand your place in the world or create an international business. Sandy Pentland taught and advised entrepreneurship classes and groups for more than 20 years, and that multicultural perspective is always a rich starting point.

SANDY PENTLAND: As I got started in my career, I realized it was all about people like us. People who are tech people. That was all that I was talking to, and there’s this rest of the world. What is that all about? And being at MIT at that time, I had the option of being able to have students who were coming from other countries. So I started to make it a real thing to get those students into my group. So I could get different perspectives because we’re trying to understand human behavior and what software does with it and stuff, and the attitudes in Europe are different than the attitudes in the US. And that’s particularly true when you move to the Middle East or India or China. And I figured, we better have people from those cultures. Otherwise, we’re not going to be doing what we ought to be doing. And I started an entrepreneurship class that I ran for 20 years at this point where the idea was this– as you come in have to start a business somewhere, not in the US or EU, and you have to touch a billion people. Now, that’s aspirational obviously, but. We’ve had one or two that have done that. So that’s pretty good. They tend to be in things that are meaningful. I mean, if you’re going to start a company, you might as well start a company that you can tell people about and have them smile at you as opposed to thinking that you’re the next robber baron or slimeball or something. Yeah, got to make the world better. What else are you going to do with your life?

CARTY: Some of the innovators he guided went on to create software that is used by hundreds of millions of people all over the world today, across health care, security, and other domains. And one key characteristic they share is their understanding that the world is not stationary. It’s always changing. Trends might repeat themselves, but a little humility is an effective dose against hubris.

PENTLAND: So developing an app company is really a walk in a very unpredictable place. You have to have a very different attitude about waking up and doing something different. People call it pivoting, but it’s more than that. It’s whole attitude has to change as the circumstances change. And so you have to recognize that the world is not stationary, it’s changing, and you have to figure out your new role in it, your new– what are you going to be doing. How are you going to add value. And yeah, some sense, you have to do that every day. Well, I think the big thing is to stay in touch with what’s happening in all the different parts of society and see the trends and some of them you think are silly. As you get older, though, you’ve seen it before. Take AI, I’ve been around long enough that I’ve seen a couple of waves of AI there’s big conferences and hype and money going into it, and then it goes away, except it doesn’t actually go away. What happens is it sort of leaks into everything else and changes everything. And so you get a little more, I would think, sort of perspective on the current bubble, the current, what’s going to happen, also on the dynamics between different markets, different countries. But you have to remain humble. We can’t predict things. I mean, it’s just amazing how bad people are at predicting what’s going to happen, which is unfortunate because you have to put your money down, right? But you do have a better idea of what are the range of possibilities.

CARTY: Sandy learned this lesson himself when working in research labs in India. He gathered some of the region’s leading entrepreneurs, and on paper, it should have been a successful venture. But what’s that old saying about the best laid plans of mice and men?

PENTLAND: I had an opportunity to live in India for a little bit and set up essentially research labs at the major universities in India, and we had a board of directors, which was the leading entrepreneurs in India and from around the world. And we were terrible, not just bad, terrible. And it motivated me to say, look, we have a sense of what needs to happen here, and we have the best and the brightest here in the room, and we can’t do it. What’s going on? How can we manage to develop program software, et cetera that does what we know needs to happen? And I think a lot of it is that we don’t understand how human groups work very well. We get derailed, we get distracted. We don’t typically think of ourselves in the correct way. And that leads us down the primrose path and bad things happen. So this is generally a problem. We’ve always had these sort of problems. We can’t talk to enough people. We can’t find enough facts. But we’ve used technology to help us all the way from– in the 1500s, people started sending letters back and forth between natural scientists, and that became science and the Enlightenment. And now, we have the internet, which started off good and maybe is it’s good, still, but it has some bad parts. And now, we have this new AI. And what are we going to do? We have to try and learn from all those previous things on how to communicate with ourselves how to decide with, among ourselves what it is we want to do without creating some horrible juggernaut.

CARTY: This is the Ready, Test, Go. podcast brought to you by Applause. I’m David Carty.

Today’s guest is International Observer and Senior Research Fellow Alex Sandy Pentland. He was named one of the 100 people to watch this century by Newsweek and one of the seven most powerful data scientists in the world by Forbes. Today, he conducts his research at the Stanford Institute for human-centered AI. He is also an advisor to the UN Secretary General’s office. Today, Sandy joins us to discuss stories, society, and the future of AI, all subjects that he covers in his recent book, Shared Wisdom, Cultural Evolution in the Age of AI. Innovators are grappling with the societal impact of technology and the challenges of creating reliable products in a world-driven by narratives, not machine narratives, human narratives. While technology offers a lot of opportunity, it also offers many chances for failure. Let’s check in with Sandy to learn why an open mind goes a long way, and oh, best watch out for his four horsemen of social failure. Here’s Sandy.

Sandy, the book’s central thesis revolves around the sense that we are a communal species that builds shared wisdom through sharing stories with each other and that innovators really need to grapple with understanding how technologies and inventions impact human society. So on a high level, what are your impressions of how technical leaders are approaching this understanding, and what can they do to strengthen it?

PENTLAND: Well, at a very high level, you look at things, the organization of companies look at what are the classic problems. And companies are organized actually using the model of the army that was developed in, like the late 1700s, hierarchical. Everybody has their swim lane. And we try to break that up a little bit, but just a little bit. And the reason is there’s too many people to talk to too many ideas. We have to actually get people all on the same page, and the army did that pretty well. But it’s a sort of oppressive structure that is there to kill innovation. They don’t want that stuff, whereas a company really needs innovation and increasingly so because the world is moving faster, technology is moving faster. Now, you can spin up things using these AI tools really rapidly. So you have to be able to pivot, move, have new opportunities super quickly. So what people are doing is trying to take the old model and stretch it a little bit. How can we make it just a little more agile? Well, actually, no, you better start adopting new tools that let you talk to broader range of people, have new models of engagement with your customers, with the people inside your company, and new ways of coming to a consensus so that you can actually act together, act with the people in your company, not just your development team, but the sales guys and the VCs and everybody else who’s actually part of the picture, as well as new ways of interacting with your customer. I mean, I’ve been on the boards of a lot of big companies, ranging from Google, AT&T, things like that. And usually, they regard the customer as those other people who have these very– almost cartoon characters. But actually, to have the right sort of products, I think, you need to increasingly engage with them in different sort of models and be able to adapt your products to local subgroups are very much on the fly. And so that’s the problem that people are facing right now. And one of the parts that’s really interesting there is that the model of the App Store or the modular platform is actually sneakily good because what you can do is you can have lots of apps out there, and individuals will customize them by adopting these apps and those apps, but not these other ones. So they’re adopting customizing your platform. And that’s actually the genius of apps. And what companies don’t do enough of is have their own apps, not new ways to make money having participatory customization of your platform. You can imagine that you have an accounting platform, and you make 10 different apps available for free– well, you bought the platform– and you watch who uses what customizations, and you engage them as a community to figure out what’s working and what’s not working. And there are some examples of people that do that. I happen to Intuit quite a bit for this reason. They go out and they hire all these accountants every tax year, 10,000 accountants, and give them software basically for free. But in return, they get to know what’s actually happening on the ground. So they actually get to see what people are doing and what works and what doesn’t work, and they build all that information into their product. So they’ve engaged with the core users in their addressable market to be able to develop the data that lets them customize better for the future. That’s a pretty good model because you’re continuously learning. You’re continuously finding opportunities. You’re letting the customers customize you. Wow, what an idea.

CARTY: Yeah, and it’s real data. It’s not assumptions. It’s not being fed by a machine or anything like that, and that can be super useful. Also, maybe that’s where the idea of boot camps arrived in the development lexicon. I’m not really sure, going back to the military example before. But in the book, you write, and I’m going to quote you here, “Our culture, government and life choices mostly turn on stories rather than logic because the social world is too complex and changeable to understand without continual observation and testing,” end quote. So some innovators might read that and say, watch me. But if we’re considering that to be a statement of fact and not just opinion, how does that magnify the challenges that innovators are really facing in creating reliable products?

PENTLAND: Well, let me just point out the history of certain sorts of innovation. So let’s just take physics, mechanics, how do you build things out of steel and so forth? So Newton had his theory, but they had to completely rewrite that theory three separate times before they were able to build bridges that didn’t fall down because the way that he had posed, it didn’t work in certain situations and had certain little hidden boundaries. So even something like how do you build a bridge turned out that we couldn’t do it, a priori. We couldn’t reason it out. We had to actually build some bridges, have them fall down, and fix them. So physics is an incredibly well-defined area where we understand the bejesus out of it. So if we can’t even get things right there, and notice that we still build models and crash them and try it, even though we have theoretically all the physics. How are you going to deal with the real world where there are memes and different cultures and the economy changes and other technologies? No, things change. And we talk about this as these four horsemen, the four major errors people make in terms of not noticing that what they’re doing used to be right but now is wrong. But that’s the core problem, is that you don’t know everything. You don’t know all the trends. You don’t know where they’re going. We’re not very good at predicting them. If we were hedge funds, would be a lot better than they are today. And so you’re in this sort of churning mess of an ocean of technology and society, and you have to not think that which way is forward. You have to continually be on the lookout, testing things not expensively but cheaply so that you know which way to turn, when there’s a leak in the boat, and things like that.

CARTY: Yeah, and getting to your point that you’ve mentioned now, there’s a sort of Western bias that presents itself. And we’ve discussed this with other guests on the podcast. So what can we learn from the rest of the world that maybe we miss when we focus too heavily on US tech and venture?

PENTLAND: Well, I can give two examples from personal experience. So living here in the Valley hear about the frontier models of AI and all the billions of dollars. But if you go to China, they’re not talking about that. They’re talking about having AI agents that do business processes. And what they want is they want to own all the business processes in all of the middle-income countries in the world, so Africa, South America, India, et cetera. If you ask who are the biggest users of Anthropic tools, for instance, it’s India. Why is that? Well, because India builds a lot of the software that the rest of the world uses. So while we’re trying to push the limit there and spend an enormous amounts of money on that, they’re trying to take the market. They’re trying to learn how to get in, what to do, things like that, and take somebody like Abu Dhabi, which I also am an advisor to. So they just released a model for completely open source, comparable to deep sea or some of the best Western models, and it’s customizable in a different way. So you can customize it to your language. You can customize it to your company. And so what I think is, we’re going to see a lot of different people releasing AI models as agents typically, not doing everything in one box, but lots of different types of box. And the rush will be– can you take over the world market? Because the countries that used to be poor, we think of them as people with dirt farmers. No, they’re all going digital. And that’s going to be, by far, the biggest market out there. It’ll take a while. It’ll take a generation. But a generation from now we’re going to see–

CARTY: Yeah, the next billion internet users.

PENTLAND: Except it’s not just the next billion. It’s the next 4 billion or something. So an example I like to give people because they always get it wrong is, what is probably the fastest growing piece of software outside of maybe ChatGPT, but it also probably including that?

And I think the answer is there’s something called the India Stack, which is the system that payments and identity, and now, web things all work out in India. And they’ve made a version of it called the Citizen Stack, which now has been adopted by 26 different countries. So they have a uniform architecture for identity, for payments, for also AI sorts of things, and that’s being used by, I think, it’s 1.6 billion people in the last three years. That’s pretty good. But you don’t hear people in this country talking about it.

CARTY: Yeah, it’s funny how we get myopic in that way, isn’t it?

PENTLAND: Yeah.

CARTY: To take it in a slightly different direction here. In the book, you talk about the concept of abductive reasoning, and that contrasts with deductive reasoning. Can you maybe, if possible, explain how that might be implemented as it pertains to the validation of enterprise-grade AI applications?

PENTLAND: Yeah, sure. So we live in a culture where logic and deduction and that sort of thing is really very highly valued mathematicians, et cetera. But actually, if you look at science, like physics, as I mentioned earlier, it’s all about experimentation. There’s a lot of things we don’t know and a lot of things that when we try to figure them out turns out it’s not right because we didn’t know about various things. I mean, the famous one is physics, most well-developed part of our whole science, about 20, 25 years ago, discovered that everything they knew was only 20% of the whole story, and there was this thing called dark energy and dark matter, and they have no idea what it is, but it’s 80% of everything. Oops, and that’s physics, where we know pretty much what we’re doing, right? So I think that sort of thing should bring a little humility to people. Abduction is that search and experimental verification of ideas. That deduction helps in trying to come up with hypotheses. But you need to take a very experimental thing to complicated phenomena. You need to actually test, measure, keep a log of it, see what’s going on, and adapt continually because it is complicated, and it’s a hubris to think that we know what’s going on, and we have all the answers if we could just write them down and prove things and so forth. And that’s the difference between an abduction and deduction. We’re taught in schools about deduction. We’re trained for 20 years. We’re still not very good at it after that. But really, what science and other things do is abduction, which is, say, I don’t know all the answers. I’m going to experiment. I’m going to find out. I’m going to trade data. I’m going to build a shared wisdom. That’s the title of the book, is that’s the process that people need to be able to be going through constantly, to be able to stay up with what’s happening.

CARTY: And we all know people that are maybe a little too deductive in their reasoning. Unfortunately, it can guide a lot of their worldview, and that can lead to some problematic opinions and outcomes, right?

PENTLAND: It happens all the time. I mean, I mentioned this group in– board of directors I had in India, and these were people who had absolutely convincing arguments about things. It’s this way. Yeah, well, except a few days later, you’d see a bunch of things that said, no, that’s just BS. I’m sorry. It’s more complicated than that.

CARTY: Yeah, an open mind goes a long way. Let’s get back to those four horsemen of social failure that you mentioned earlier, and those are unseen change, rare events, one size fits none, and myopia. I didn’t even realize I was mentioning one of them when I mentioned myopic view earlier. But can you explain what those are and why they’re relevant to our product leaders and innovators?

PENTLAND: Yeah, sure. I like to give financial examples because they’re very clear I think. So for instance, banking regulations, the whole notion of withdrawals and borrowing. And so it’s based on the idea that people are acting independently. So you don’t get runs on the bank if people are acting independently. But as we saw, for instance, with Silicon Valley Bank, now that you have social media and all your depositors are on the same Reddit, Subreddit, right? You can get runs on the bank that are digital, and the regulations don’t even anticipate that. So this change of having your customers not be independent, but actually being able to coordinate with each other is responsible for bank crashes, meme stocks, and also in a certain sense, for the 2008 crash, because people occurred to them, they started talking and saying, you could just walk away from your mortgage. It’s OK. If you’re underwater, you’re underwater. Just go. And that wasn’t supposed to happen. And so you got this coordinated action in lots of places. So that’s the unseen change where they were developing rules on assumptions that slowly became not true, and the rare event is when that typically breaks. So think about this as this. You’re building on a foundation, which is your assumptions about the way things work, and it begins to change, and it’s like an earthquake. And so 2008 Silicon Valley crash, and there’s a number of other ones like that in the tech space. So PalmPilots used to be this way. There’s a whole bunch of different companies that have gone the way of the dodo, because they assumed that the way people were using it was going to stay the same and their competitors adapted. So that’s the rare event. And we hear about this. There are certainly books about this and so forth. The grace ones or black swans, they’re often called. And then the one-size-fits all is, I think, a lot worse than people appreciate. So in this age of machine learning and AI and so forth, it’s very tempting to say, oh, all the customers do this. This is the best rule on average. And so banks do this. These are the loan terms for everybody, except different communities actually are very different. So for instance, just as an example, financial example, all the banks were setting loan terms that were uniform across the whole country. And Capital One came in and said, hey, wait a second. This really screws over all the Latino people because they can’t qualify quite the same way because they’re not that good at English. Oh, and so they started a company to do the same thing, but for Latinos. And now, they’re this huge business. And there’s a number of other examples like that where people didn’t see that there are subcommunities. They were setting a uniform rule because it’s easier. And in the tech industry, often what happens is you set rules that seem sensible to you. But they’re not necessarily sensible to your customers. Your customers come from lots of different backgrounds. They want lots of different things. You have to have a way to customize for all those customers. Otherwise, you get this one size fits none where there’s just a few people that actually really like what you did, and everybody else thinks it sucks, but they put up with it. And that’s, again, as I mentioned at the beginning. App stores are actually pretty interesting, not as ways to extract money, but as ways to see what communities there are and what their preferences are so that you can slowly evolve your product to match the preferences of your customers. And the final one was this myopia. You just don’t see things coming. This happens all the time. Somebody has a new product, a new technology. There’s a fad that takes off and suddenly people are buying these things versus that things. And of course, there are large-scale things like the 2008 crash. COVID is more recent, et cetera, and you have to be aware that even if you don’t think you have assumptions, you do. And the way you become aware, the way you do all these things, is by engaging with your customers in a way that’s hopefully very cheap but allows them to express their preferences and you to evolve relatively dynamically so you’re not hit from behind by something you didn’t expect. And when the earthquake happens, you’re off someplace else, doing something different, and you get to laugh at all the poor jokes that weren’t that way.

CARTY: Yeah, we could probably do a podcast episode on each of the four horsemen because there’s such interesting areas, and you also don’t know when you’re connected with your community of users. They can uncover all kinds of– showstopping kinds of issues. I mean, it can really run the full spectrum there.

PENTLAND: Absolutely, yeah, no. It was one of the appalling things when I was on this tech board for Motorola, is that they would release a phone and not have any data about users using it for six months. By that time, if they got it wrong, they were screwed.

CARTY: It’s a recipe for disaster today. That’s for sure. So we know that technology and AI, they’re capable of producing harmful outcomes, such as exacerbating financial inequality, racial profiling in criminal justice systems, or any systems, really. But it can also be a unifier toward addressing some difficult problems if it can appeal across different cultures, geographies, that sort of thing. And in fact, human story sharing and decision-making inventions have their own messy history, which you mentioned in the book, such as war, cults, oligarchy. So if story sharing can exist on this sort of wild ethical spectrum, what does that mean about our ability as a species to embrace AI, and maybe how can we do that safely?

PENTLAND: Yeah, well, the first thing is I’m reminded of a discussion I was in, where someone was making these very points, and the justice minister of Kenya happened to be in the audience. And he stood up and he said, what you’re saying is probably true, but have you seen our current system? I mean, people do all this stuff too, and we don’t even keep track of it. So the key thing is, again, keeping track of what your systems are doing, auditing them, and asking those questions. And this is more important than ever, is you get asked these questions, and you have to be able to answer them with certainty and immediately. Otherwise, you get hit by a storm in the social media and other places, people will pile on you. I was somebody who helped Anheuser-Busch recover from their Bud Light. I mean, it was just an example of they were myopic. They thought that everybody wanted this sort of thing, and they forgot that a lot of their customers are not on board. And so, hey, now, what do you do? That’s bad. So you need to be able to test things. You need to be able to see what’s going on continually. So we’ve done a couple of things. Let me give you an example. We built a system. It’s a modular system. It’s open source. You can just use it. People are using it for– it’s called Deliberation.io. just look at it, codes there, and a number of papers. We convinced Washington DC, the city of Washington DC, to adopt this, to ask the question of, how should AI be used in government? So that’s a really salient part of AI. Oh my God, the robot overlords. But the thing that came out of it was really interesting. What people? And these were single moms with two jobs. It was not like the elite talking, and that’s by design. What they wanted is they wanted AI to help represent them to the government and get the things that they were owed the be part of the programs without all that paperwork because it’s really complicated. So AI for people was the thing that the citizens, the regular citizens in Washington DC, thought, and that’s what we see fairly broadly, too, is it’s complicated. There’s scams everywhere. It’s going to get worse. What I’d like is I’d like something that’s on my side that represents me in the same way that say, a doctor does or a lawyer is supposed to do or things like that. So this notion of personal AI, and I think that’s an enormous game changer. And I’ll say why as we go on here. But this idea that it’s not them that own it’s me that owns the AI, and maybe I’ve got buddies that we share costs, and we trade tips with and things like that. And that sounded to me like consumer reports, which probably people know. So it’s basically a community of a few million people. They put in a little bit of money, and they test products to see which things are stupid and which things are good buys. And so we’re working with them to build an open-source, unlicensed personal AI that helps consumers to defend you. It’s called LoyalAgents.org. And we’re just starting with consumer things. But we also hope to do health care, government, things like that so that you have somebody who’s going to defend you in this world of AI. So if you’re interested in that, we’d love to work with you, help, et cetera.

CARTY: I think a lot of people can certainly relate to the idea of AI helping them cut through some bureaucracy and achieve an outcome, but it does get into an interesting question here because when it comes to this notion of preserving human autonomy in the way our data is consumed and in the way that we synergize more broadly with AI, how can we recommend that organizations take some steps to make this a constant priority and to keep that in mind?

PENTLAND: So that’s a really interesting and absolutely critical thing, because people are going to try and game this in lots of ways. So in law, there is this thing called being a fiduciary. And this is what your lawyer is supposed you’re supposed to represent you, not them. And there are legal tests for what counts as a fiduciary. And if I’m going to have an AI that represents me, it better pass those same tests. It better do this. It’s called duty of loyalty. It had better fulfill whatever it does on my behalf, and this is a well-defined legal idea and framework that says, it’s for me, not for you. And what we’re doing is we’re trying to customize this so that it applies to software. It’s not a big list, but it’s an interesting thing. So currently, you see things like MCP, which is communication between agents. And so we’re doing human communication protocol. So how do you express your preferences in a way that those AI agents will pay attention to and get you what it is that you want rather than them? Like I said, that’s LoyalAgents.org website, which is a lot of the big AI companies, because they’re worried about this, and a lot of the NGOs. The reason the big companies are worried about this is that if you have an agent that seems to represent a person, seems to represent you, but it’s self-dealing. It’s maybe doing other things, then you’ve opened yourself up to not just lawsuits, but class action suits. So those run into the billions of dollars. Nobody wants to do that. What they want to do is they want to have something that meets the legal criteria, that makes them safe in helping you do things. And so that’s a good dynamic. I want the companies and the manufacturers of AI to be a little bit of feared so that they build things that actually represent us legally. And part of that also is this business of bias you’re talking about and fairness is– they have to be able to for these tests– they have to be able to pass a test that shows that they’re not biased more than is typical or that they’re not unfair more than is typical. And so embedding agents and AI in the existing sorts of frameworks we have for human agents is the goal here. That seems to be something that for the last century or two, we’ve developed these rules and these ways of making sure that the person that works for you actually represents you. It doesn’t always work, but we’ve thought about it, and now, we’re going to have to extend that to software agents.

CARTY: Along the same lines, when it comes to regulations and privacy preserving technology, what are we lacking in what consumers have available to them today? And how can organizations take a more proactive approach maybe to prioritizing the safety and security of their customers?

PENTLAND: Well, so the thing that’s really interesting about having AI agents that represent you is, they don’t have to share much data. They just have to say, I want a blue car. They don’t have to say why where they live, blah, blah blah. They just have to be able to be certified in representing you. And so I mentioned that we’re doing this with consumer reports. So we’re deploying agents for those people that will represent them, and then the agents will trade tips about what worked and what didn’t work, stories about how to get past the scams and what to tell the government and things like that. But what they’re also doing is keeping control of the user data. So the amount of data that leaks out about you is much less because all you’re doing is specifying preferences. And incidentally, it’s more data because it’s yours, and you’re not sharing it. You can have local AI, personal AI that does a better job of representing you than they could. So there’s actually advantage to you. And this is a problematic thing for a lot of companies. And in particular, it’s a problematic thing because the role of advertising becomes very different. Advertising is to try to convince you to do things. But if your agent is actually looking at the numbers and making decisions that represent you, where’s the role for advertising? So a lot of people are beginning to realize this. Google realizes it. Andreessen Horowitz realizes it. The advertising industry is going to change a lot. And what will happen is for small things, advertising will become negligible. For big things, like buying cars and homes, you need to have agents that are more like buddies. And I think that’s a main theme, is you need something that’s helping you, not something that is representing a company. And so the idea of building things that are helpful to individuals is, again, the thing that, I think, is the hopeful part of the future. And a lot of the evils we see today come from the fact that it’s an advertising click-driven ecosystem. Maybe we can begin to move away from that in a substantial way.

CARTY: Yeah, fascinating, I appreciate your perspective. Looking on the bright side and a lot of what we’re talking about today, and I think this would be a great final question for you here is what is your outlook for this complicated intersection of human agency, AI adoption, cultural disparity, corporate opportunism, as you mentioned, and government oversight. There’s a lot of competing interests, a tangled web. Where do you think we’ll end up?

PENTLAND: Well, predicting the future is hard. But I can tell you where I’d like to end up and where I think there’s a good chance we can do it if we’re all realize that it’s a good place to go. I’d like to leverage this personal agents idea to be able to, first of all, put people back in control of their data and in control of the interaction for buying things. It’s like when you walk into a store, you decide what to buy. Your agents should mimic that in a certain way, without a lot of influence from other sorts of things, and then the other thing is, when you think you’ve been cheated, it’s often really difficult to prove it. It’s difficult to get made whole again. And so I think what you’re seeing in government, you’re seeing as a sort of opinion that is beginning to come around to being pretty universal is, there have to be audit trails for all the things that these AIs do. Now, it sounds like that’s, oh my God, get the accounting firm in here. No, no, no, no, this is like we keep track of when we spend money. We bought this thing for this amount of money, paid that blah, blah, blah. We do that for everything. We also keep logs of computation. We keep logs of lots of things. We need to keep logs of what the A’s are doing, and then you need to be able to have tools that when somebody says you’re discriminating against x, you need to be able to say, OK, look at the logs. Are we discriminating against x? And you should be able to get the answer back. And ideally, within seconds, to say, no, actually, when we looked through all the data, this way and it’s better than the standard in the industry, so sorry, you’re wrong. Bad impression. And I think that increasingly that will be important because remember that the law things the lawsuits all that will also be benefiting from AI. So they’ll be faster, meaner, quicker. So you better be able to deal with that onslaught also. And so this idea of having audit logs that are queryable perhaps publicly to be able to say what’s working, what’s not working is also part of being engaged with your customer. Like if you have audit logs, you should be able to say what’s working and what’s not working in your product. And having ways to engage age groups of people like the consumer reports people or other sort of people that have their own agents to be able to have them express their preferences to you about what they’d like to see is a great way to find new opportunities and continually evolve your product. That game will get a little bit different, because you’d be dealing with the agents, and not as much with the people. People are notoriously unable to express their preferences, but the agents have different sorts of problems. But some of them are very complimentary. So you ought to be able to do a better job of building an ecology where you’re helping agents do a better job. And so they help you with that, doing the better job. I like to think of it as a sandbox. You’re going to have a sandbox, which are your customers, and what they’re doing is they’re helping you be a better service provider or a better product provider. And that’s a deal that’s different than today, where typically, you say, well, here’s the thing, buy it, and maybe we’ll talk again. This is something that’s really more of a co-development mindset. And I think that’s enabled by this notion of having personal AI that can help deal with the complexities of that follow-up with things, avoid traps, and so forth.

CARTY: Yeah, you make it a one-way street with your customers at your own peril, basically.

PENTLAND: That’s right, yeah. You’d really like to have them helping you with product development and discover new opportunities.

CARTY: And you can be sure they have opinions. That’s a certainty.

PENTLAND: Absolutely, well, so one more thing to mention is that, so we have done things like this for government. And it also works for this product development. So it’s Deliberation.io. I mentioned it earlier. It’s a way to get people to express opinions. That’s where this idea about an agent to help you deal with the government came from. It came not from tech guys. It came from customers. And it’s an interesting way to have a conversation about what people want without flaming, without influence from influencers and so forth, and also, incidentally, to educate all of the consumers or all the citizens about what everybody else thinks so that there’s a lot more consensus about products, about the way things should be. So take a look at it. It’s a good thing. Again, open, free software is there.

CARTY: Here, we go, Sandy. Lightning round questions before we let you go. First, what is the most important characteristic of a high-quality application?

PENTLAND: Engagement with customers. You got to know what they want. You got to be able to customize it for them but without doing like a million features. That’s why I like the example of app stores.

CARTY: Sometimes simple is better. What should software development organizations be doing more of?

PENTLAND: Well, I think that they should be using AI to be able to sample opinions, to be able to see what’s happening more broadly in their corporation, but also with their customers. So for instance, that’s the stuff in Deliberation.io where AI is helping you find the things you need. It’s not giving you facts but connect to other humans. It’s promoting the discussion within and outside of your corporation.

CARTY: That makes sense. On the flip side, what should software development organizations be doing less of?

PENTLAND: I think this notion of locking things down, adding features, assuming that this is really it, and you’ve got to double down on what you’ve got now is a fundamental mistake. It’s like those earthquakes. You make the plate more and more rigid, and then don’t do it.

CARTY: Exactly. And finally, Sandy, what is something that you are hopeful for?

PENTLAND: Well, it’s this personal agents idea. As we get agentic AI, it’s not at all crazy. We already see things running on home computers, on phones and things like that. And so having AI to defend you against all the other AIs, I think is a common thing. And as ill-intended people become more savvy with AI, it’s going to become more and more important.

CARTY: Well, this has been a fascinating discussion, Sandy. Really, really appreciate you joining us. Thank you so much.

PENTLAND: Well, thank you for having me. It’s great to have the opportunity.

CARTY: What a great conversation with Sandy Pentland. We really appreciate him joining us. You can find his book, Shared Wisdom, Cultural Evolution in the Age of AI, as well as the other resources that he mentioned during our conversation in the podcast notes. Thanks to our producers, Joe Stella and Samsu Sallah, editor Ian Lippincott, and graphic designer Karley Searles. Go ahead and subscribe to Ready, Test, Go. You can find us on most podcast players. Drop us a review. It really does help a lot. You can also subscribe to the Applause YouTube channel. The handle for that is Applause.com all spelled out. Or, go ahead and reach out to us directly at [email protected]. Thank you so much for joining us.